The Dangerous Misrepresentations that Define Television’s Scripted Crime Genre

A Comprehensive Study of How Television’s Most Popular Genre Excludes Writers of Color, Miseducates People about the Criminal Justice System and Makes Racial Injustice Acceptable

A report by Color of Change and the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center January 2020

Americans’ perceptions of crime are very much at odds with the reality of crime in America. As just one example: while the crime rate has dropped dramatically over the last 20 years, the number of people who say crime is going up is steadily increasing. These misperceptions are dangerous. Distorting the truth about crime and race turns the public against criminal justice reform and increases the scapegoating of people of color. Does television play a role? Is scripted television essentially a PR machine for the police?

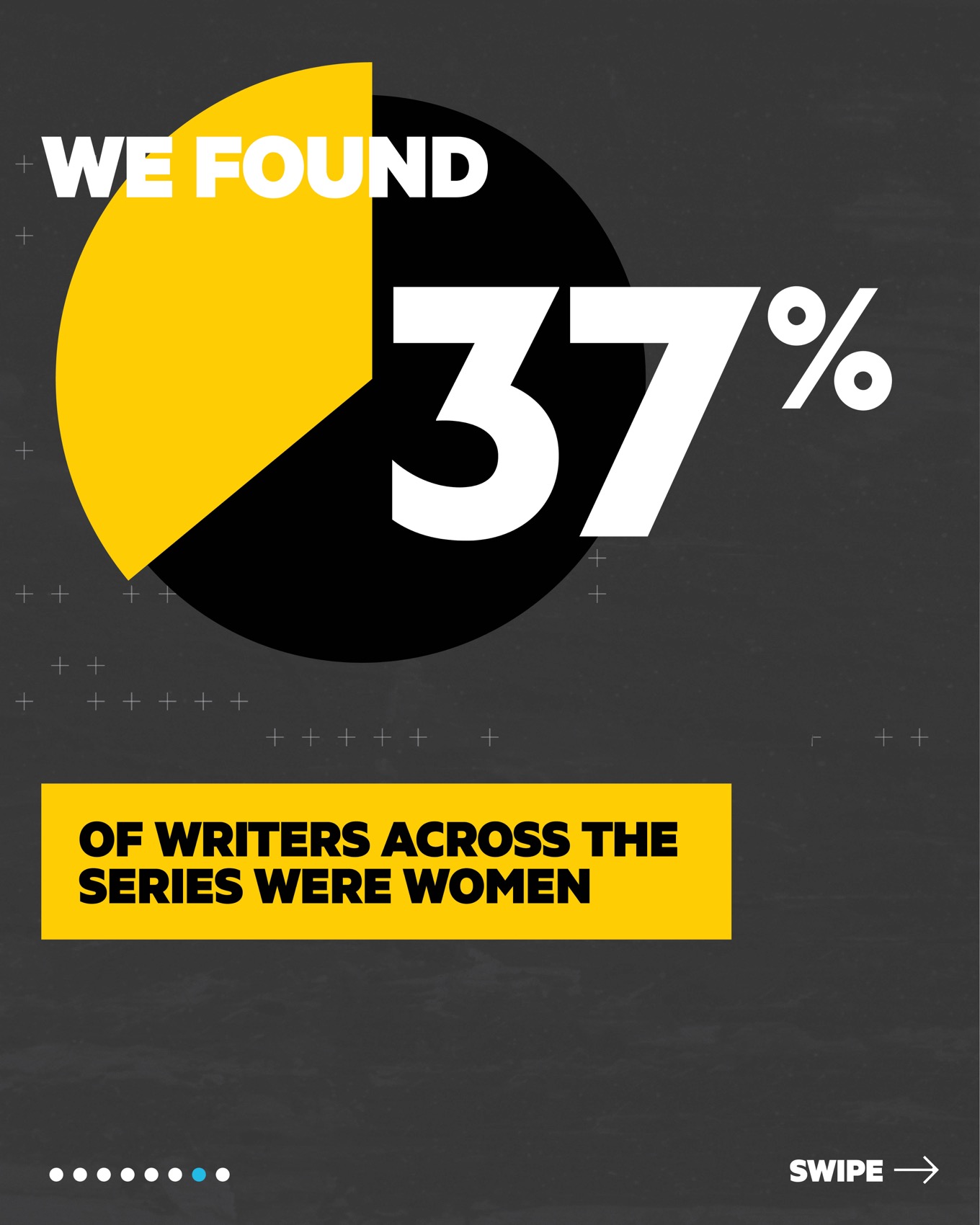

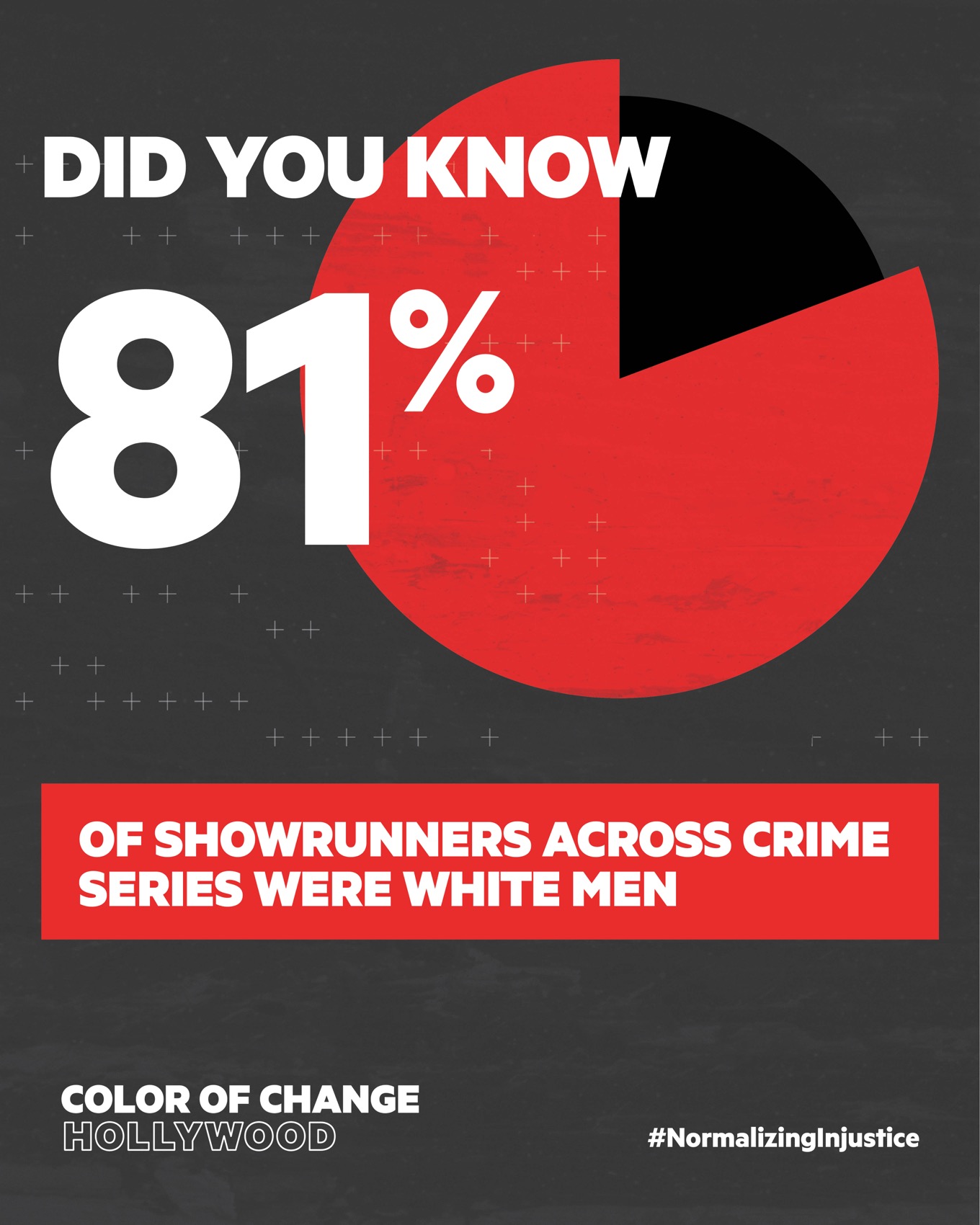

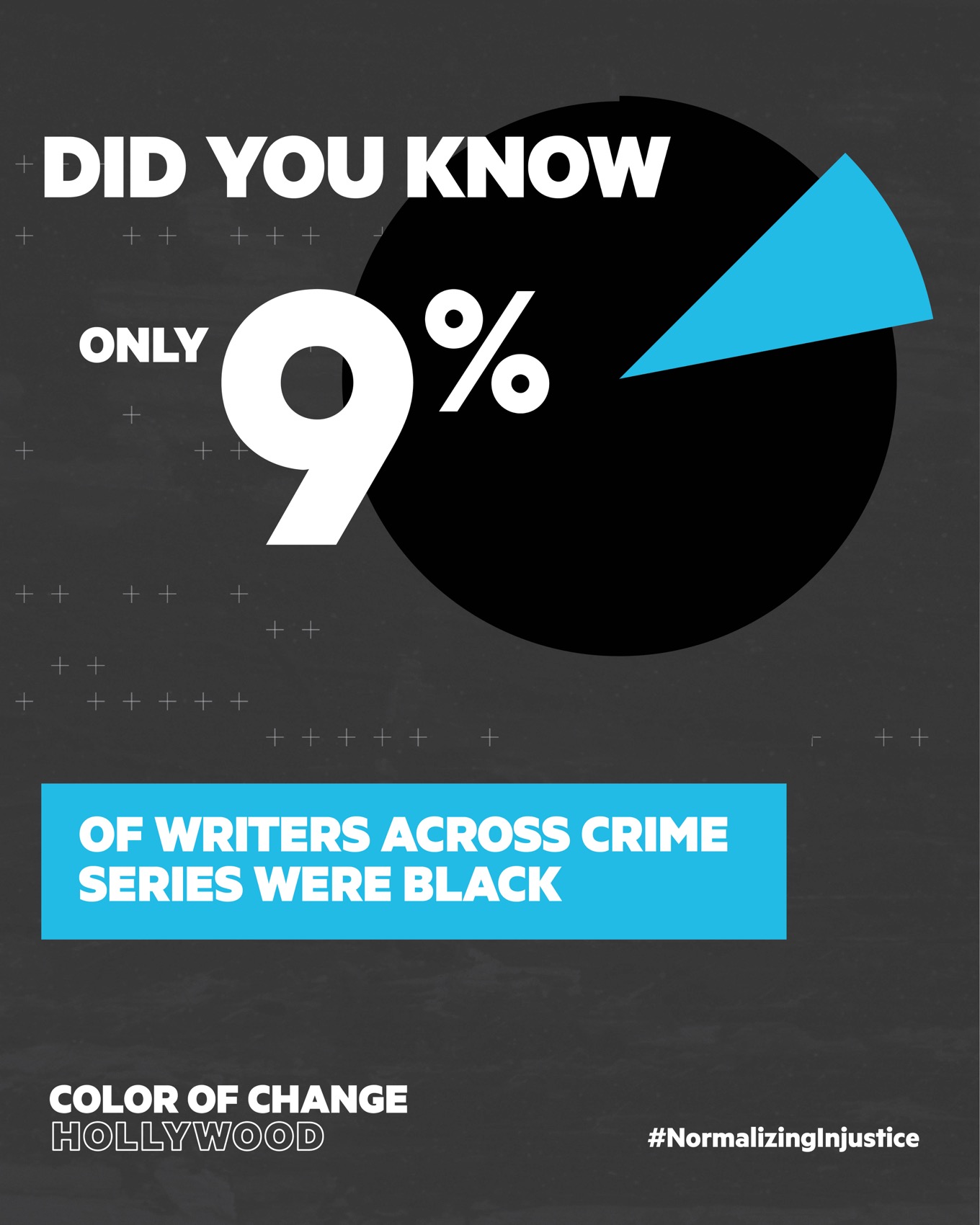

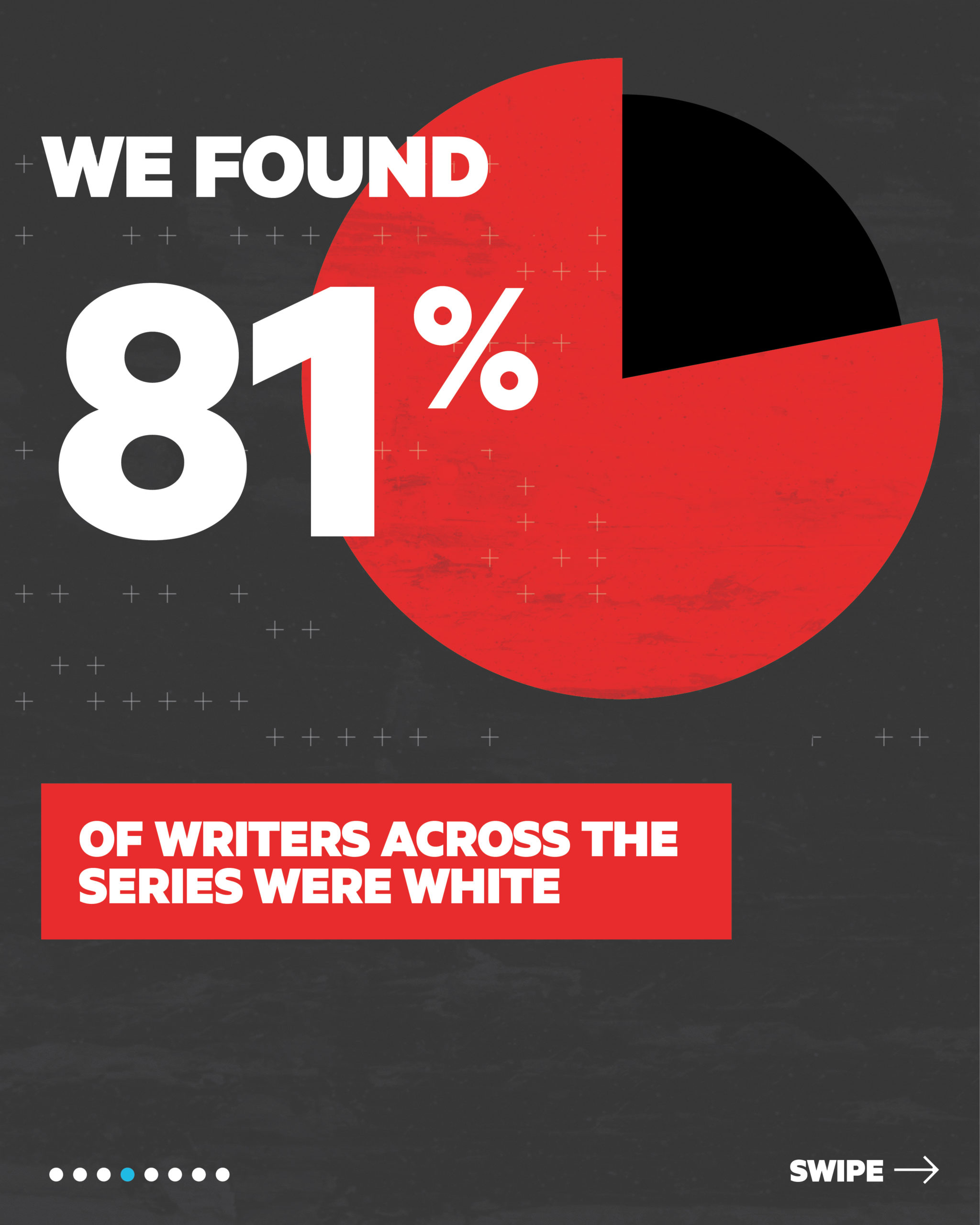

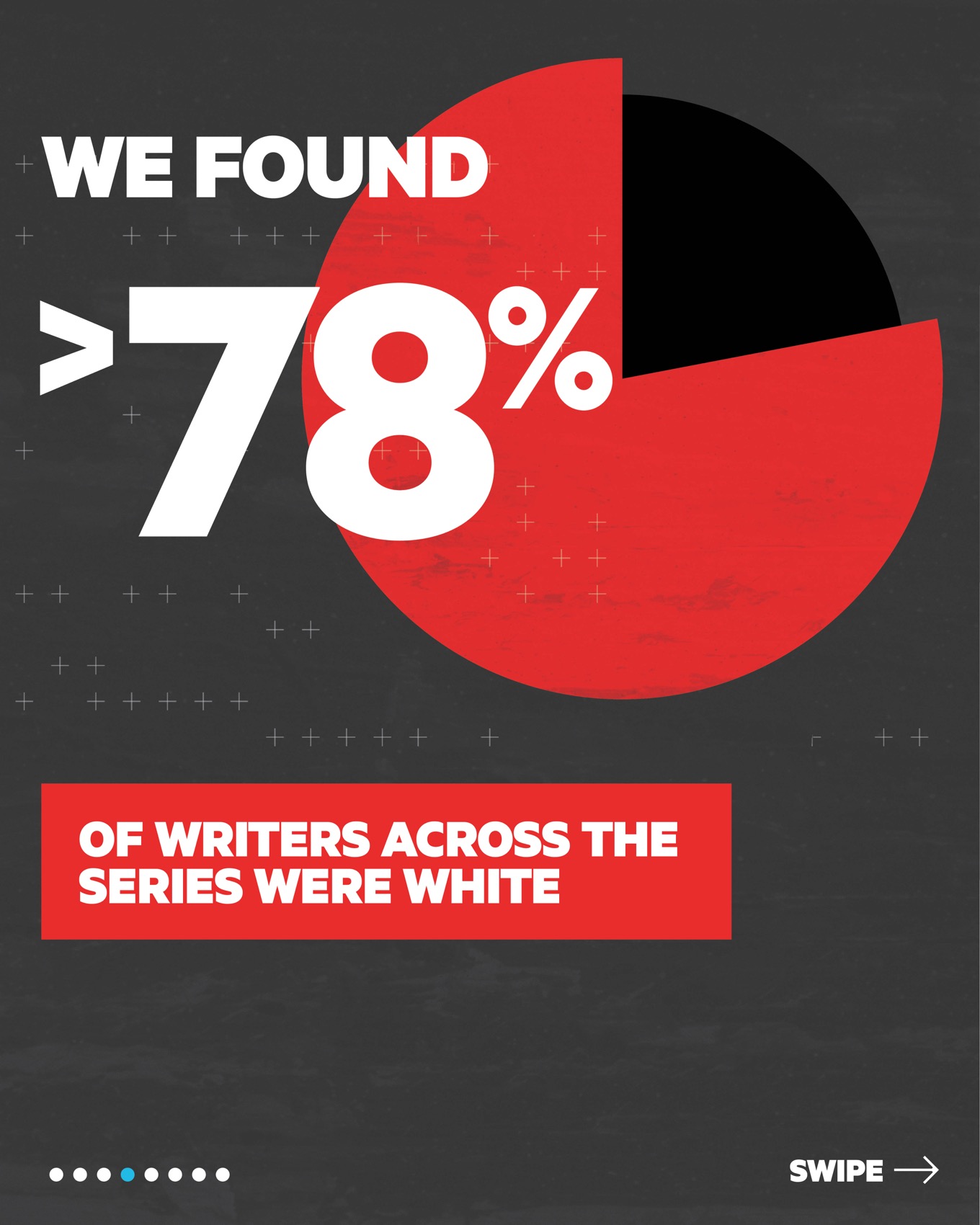

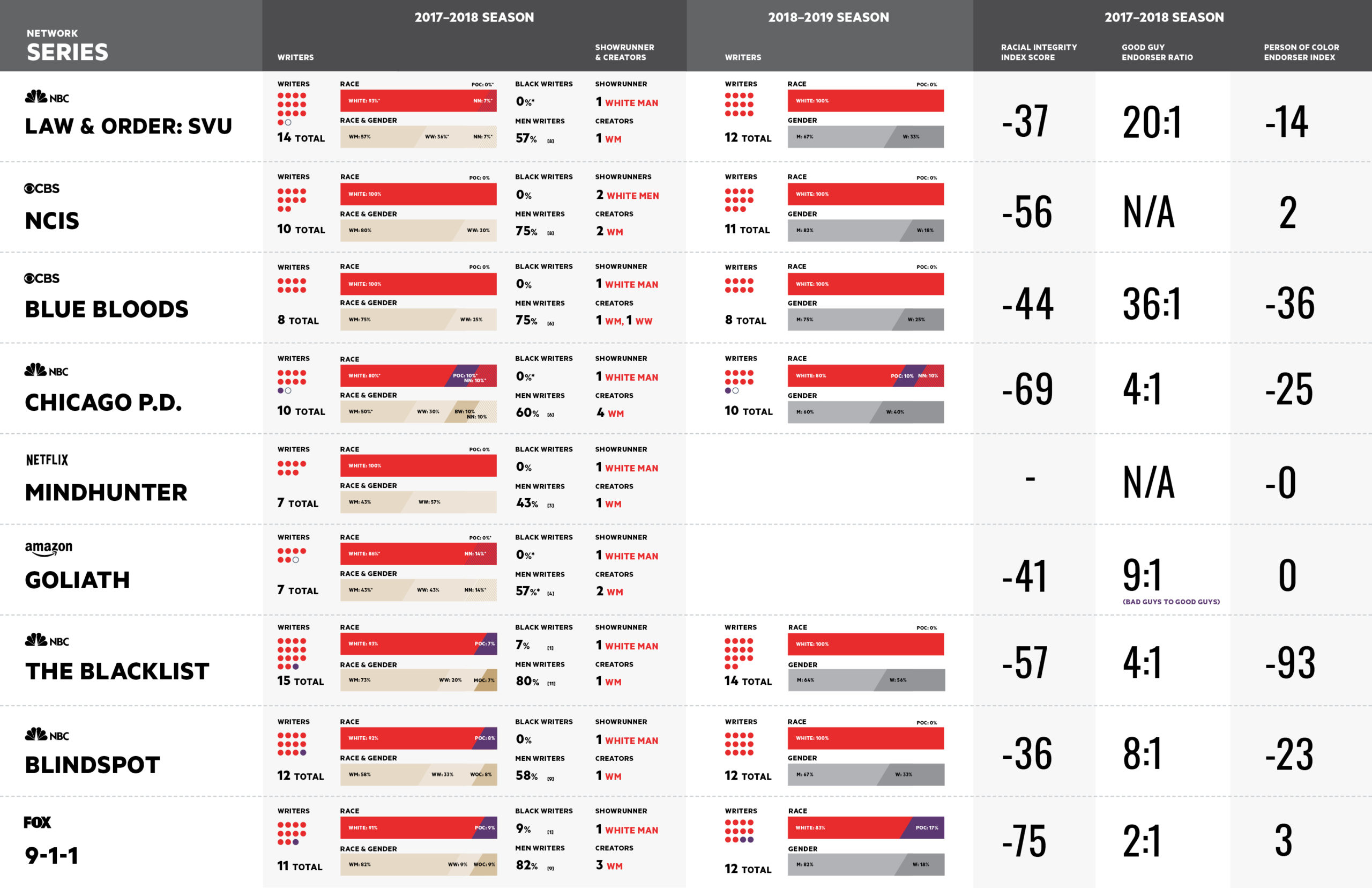

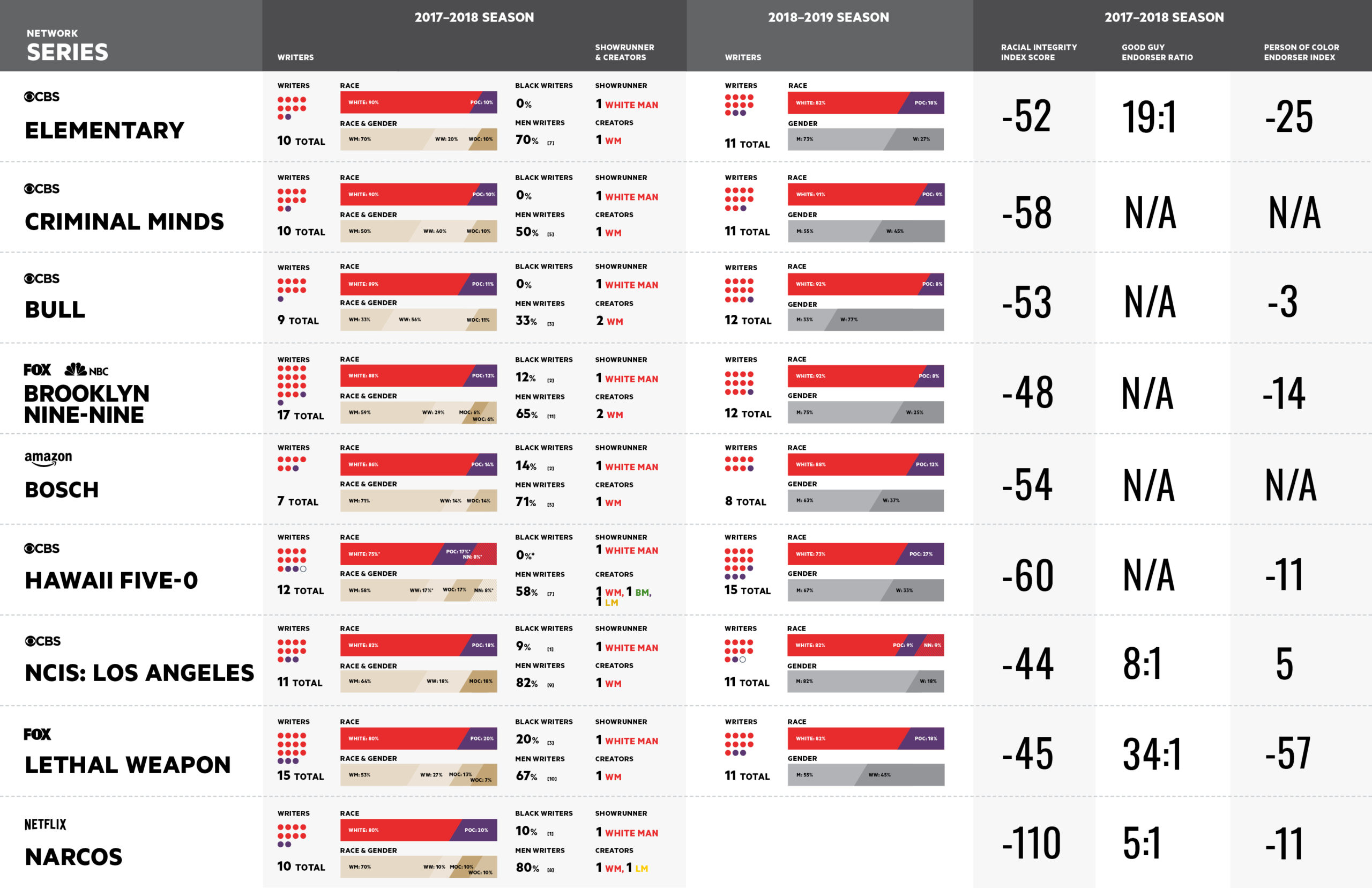

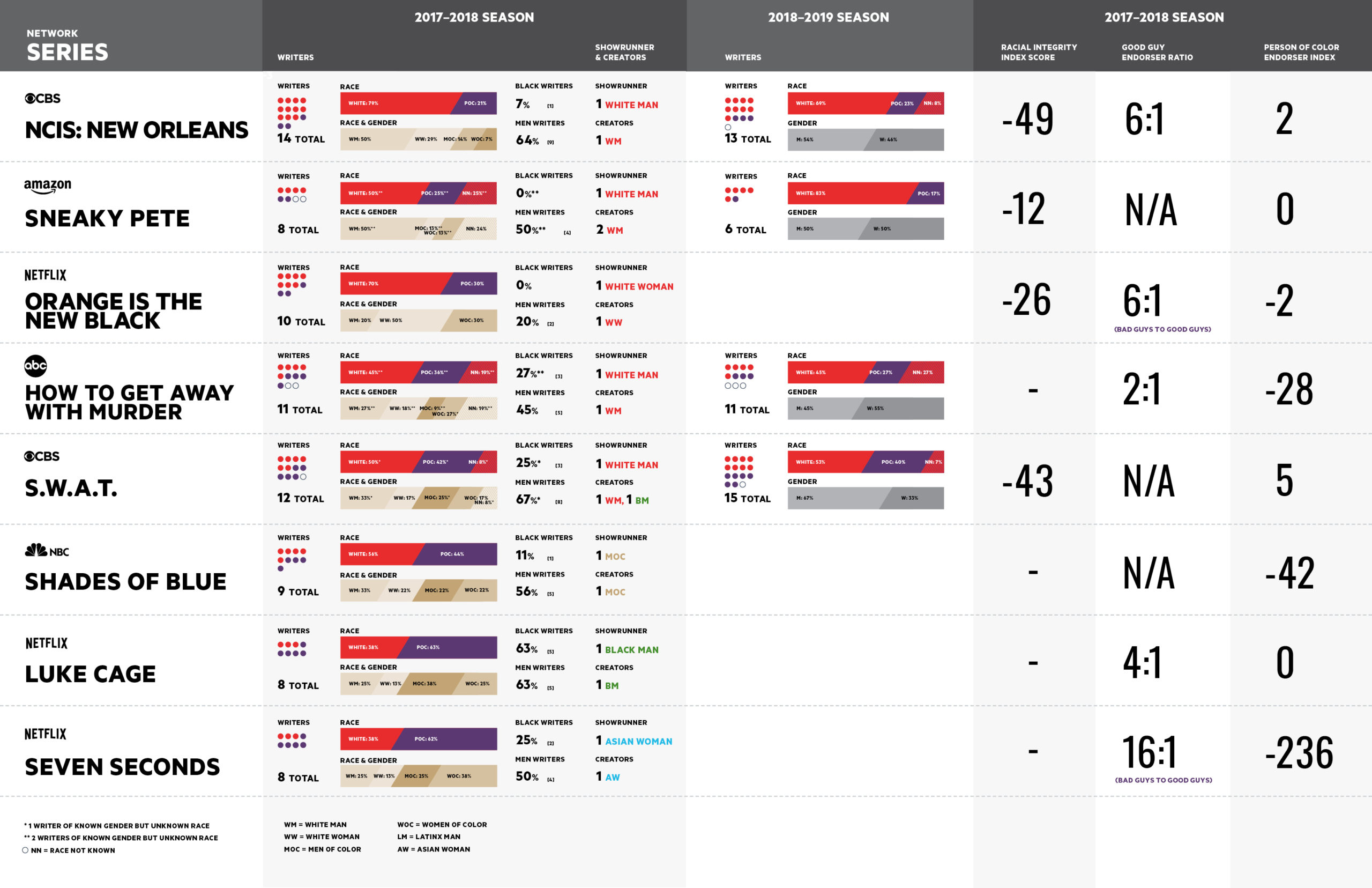

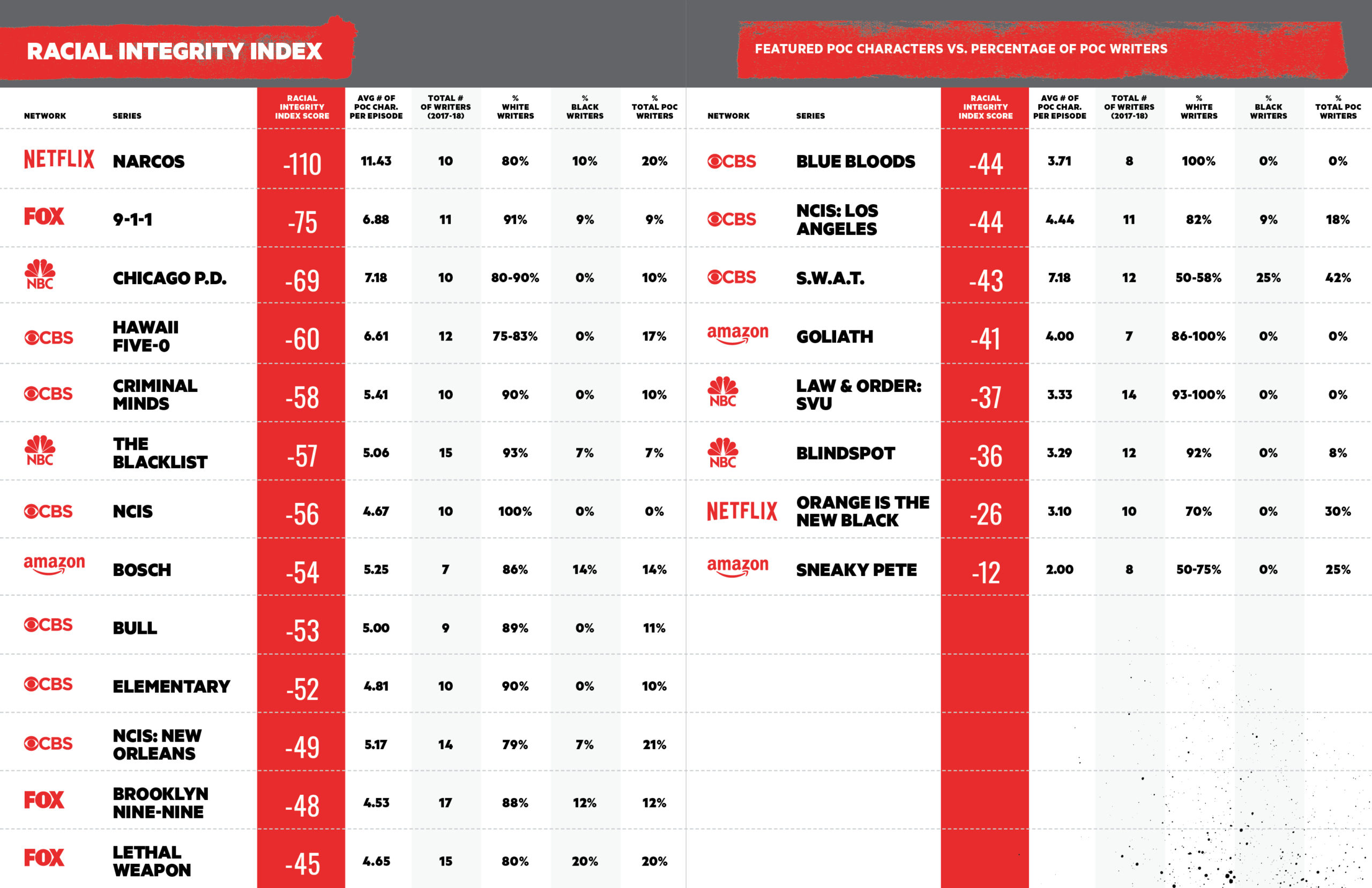

Normalizing Injustice is a first of its kind study of how scripted crime shows represent the criminal justice system. The study analyzed 353 episodes from 26 different scripted series focused on crime from the 2017–2018 season, while also identifying the race and gender of the 41 creators, 27 showrunners and 275 writers behind all 26 series. The report further identified the shooting locations for each series and the police, military or other consultants each series employs for advice.

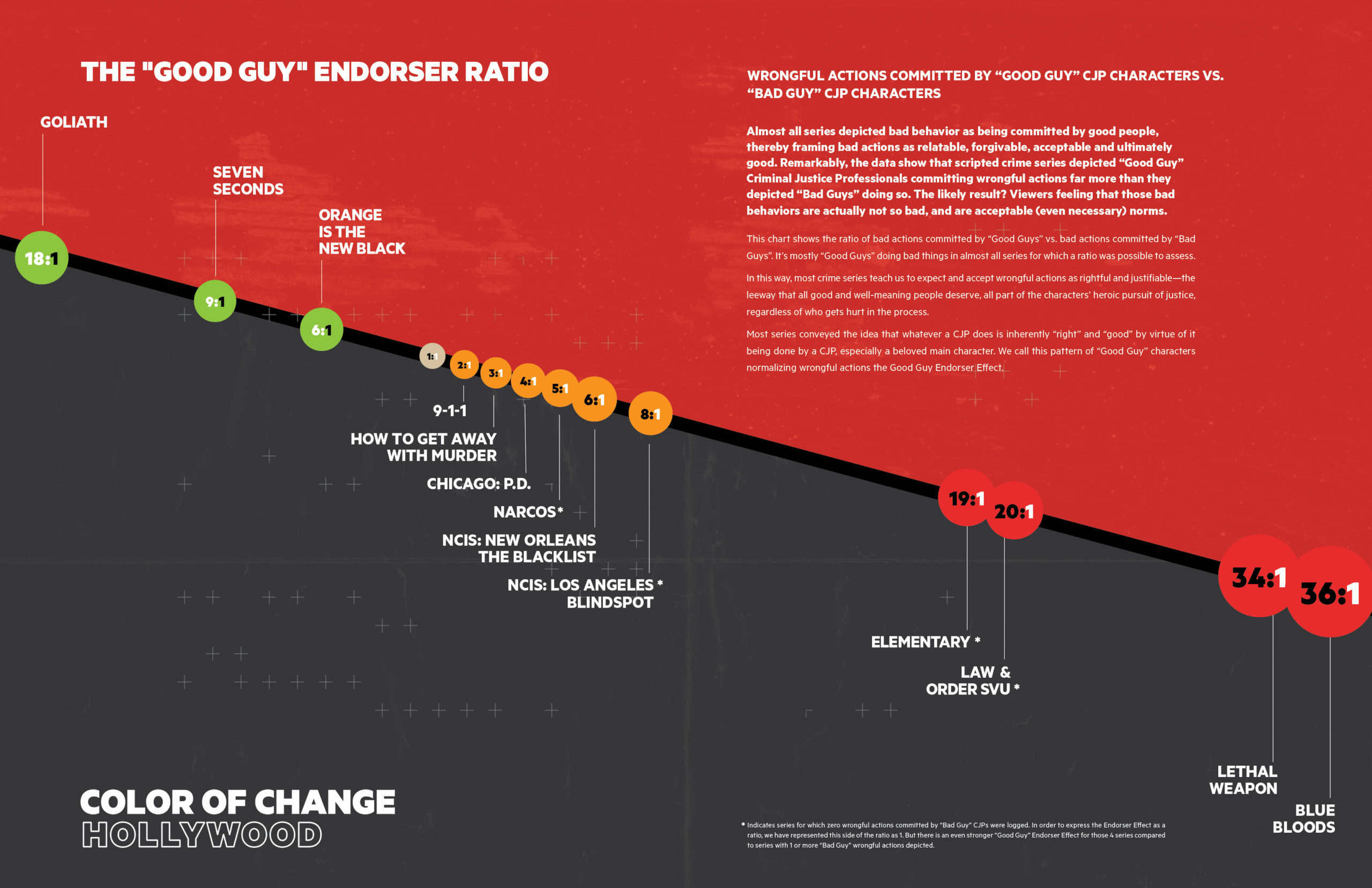

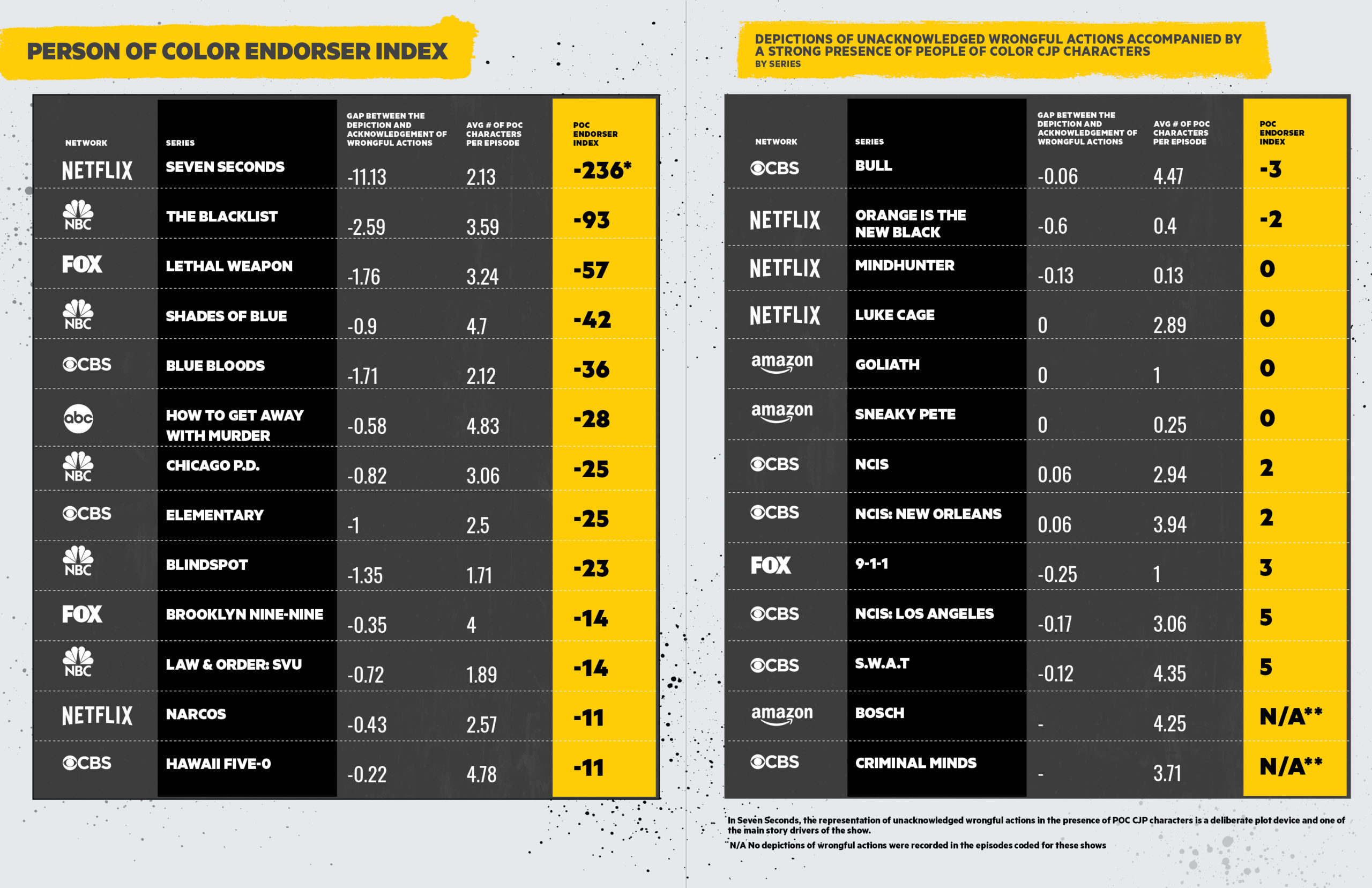

Normalizing Injustice found that the crime TV genre—the main way that tens of millions of people learn to think about the criminal justice system—advanced debunked ideas about crime, a false hero narrative about law enforcement, and distorted representations about Black people, other people of color and women. These shows rendered racism invisible and dismissed any need for police accountability. They made illegal, destructive and racist practices within the criminal justice system seem acceptable, justifiable and necessary—even heroic. The study found that the genre is also incredibly un-diverse in terms of creators, writers and showrunners: nearly all white.

"Viewers will change the channel if we make the crime victim Black, so you'll have to rewrite those characters and make them white instead."

That is an order we know some writers have been instructed to follow by showrunners, producers and network executives. It is one of many deeply disturbing stories we have heard while looking at what goes on behind the scenes of one of television's most popular genres—scripted crime and legal series.

This report presents the results of a landmark research study that examined depictions of the criminal justice system—as well as portrayals of people of color, women and issues of race—in popular American crime TV shows. The study included 26 different scripted series focused on crime from the 2017–2018 season, broadcast on both networks and streaming platforms.

We need new standards to be socialized and implemented across the industry. Those standards must be backed up by meaningful incentives that reward responsible storytelling, as well as by real consequences that hold executives accountable when they enable (or even encourage) demonstrably harmful stereotypes and inaccuracies to go unchecked. At the same time, the many showrunners and writers who want to do better must be supported in doing so. They must be given the time, talent, resources and approval required to break convention and change course.

These are going into our bloodstream, these stories. They go into our DNA. They become a part of our mind, our memory. So we really have to be more rigorous in our examination of what we accept.

Ava DuVernay,

Writer, Director, Producer